Kingston’s Food Policy Bites

Issue 2: November 2024

Welcome to the second edition of Kingston’s Food Policy Bites!

The City of Kingston’s Department of Health and Wellness is tasked with facilitating policy, systems, and environmental change to benefit the people of Kingston. We know that effective policy is built on transparency and consensus — but we also know that policy can be complicated and hard to read. To that end, we want to make the world of food policy more accessible and relevant to our City. That’s why we’re testing out a new initiative: Kingston’s Food Policy Bites.

After an inaugural edition on the Farm Bill, this month we’re pivoting to look at how one type of local legislation might impact food access.

Can Business Tax Breaks Improve Food Access?

Increasing food access through increasing, expanding, or modifying food retail locations is a hot topic. Between the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, a public-private partnership established by the 2014 Farm Bill and reauthorized in 2018, and the 90 policies that came up under a “food retail” inquiry on the Healthy Food Policy Project’s database, many policies and programs have been created in recent years to incentivize the opening of new stores or to encourage existing stores to offer a wider range of food staples and healthy items. But do they work to increase food access, and is this something we should consider in Kingston?

Let’s first take a look at food retail locations in Kingston.

Kingston Food Retail Landscape

According to the NYS Agriculture and Markets, there are 84 “food retail” locations in Kingston. However, using the SNAP store definitions and database, there are just 3 full service grocery stores (that also accept SNAP)- the Hannaford located in uptown Kingston (a “super store”) along with Kingston Meat Market and El Mercadito (“grocery stores”).

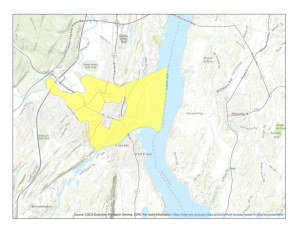

Given this lack of grocery stores within the city limits, 3 out of the 8 census tracts are considered “low income, low access” by the USDA Economic Research Services, which means that a significant number of households are more than 1 mile from a grocery store. These neighborhoods are largely concentrated in the Midtown, Ponckhockie, Rondout, and Wilbur neighborhoods (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Low income, low access census tracts in Kingston

Source: USDA Economic Research Service, ESRI. For more information: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/go-to-the-atlas/

Yet walking just a mile can be challenging for some. While Kingston has made and continues to make great strides in recent years to increase pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure, and UCAT bus service is free, there are still barriers to traveling more than 1 mile and back with groceries, such as:

- Physical ability to walk or bike, or the time to do so

- Sidewalk maintenance

- Bus routes and times

- Limited ability to carry bags and voluminous items, like fresh produce

For these reasons, the standard for “low income, low access” for households without a car is ½ mile. Using this data point, there are 5 out of 8 census tracts where a significant number of households do not have a vehicle and are more than ½ mile from the nearest supermarket in Kingston according to the USDA Economic Research Service (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Low income, low access census tracts without access to a car in Kingston

Source: USDA Economic Research Service, ESRI. For more information: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/go-to-the-atlas/

So Are Business Tax Breaks a Food Access Solution?

A quick glance might suggest that the simple solution is to open new grocery stores in these underserved areas. However, it’s complicated.

One major hurdle in most cities is that it’s illegal to open a grocery store in residentially-zoned districts. Fortunately for us, Kingston’s new Form-based zoning code made it possible for new businesses to open in many more areas throughout the city with the legalization of neighborhood businesses.

But this doesn’t guarantee businesses will open, even though they might be sorely needed by underserved communities. Opening a business is complicated, especially one with an industry profit margin of 1-3%, like a supermarket. There is also the phenomenon of “supermarket redlining,” a term used to describe major chain supermarkets’ disinclination to opening stores in lower-income neighborhoods, influenced by perceptions that these areas are at higher risk due to concerns about crime, social instability, and lack of profitability.

In response, some cities have developed “incentive policies” that are supposed to encourage new businesses to open. Let’s take a look at those.

Success Story? Prince George’s County, Maryland

Prince George’s County, Maryland implemented a policy that provides an 80% reduction in property taxes to any stores that sell fresh produce, meats, and dairy products in “healthy food priority areas.” (These are regions where people mostly make a lower income and also lack grocery store access). Since 2017, several new grocery stores have opened throughout the county, which is part of the Washington D.C. metroplex. This reduction remains in effect for up to 10 years for participating stores.

Not So Successful: Camden, New Jersey

Camden, New Jersey, codified a policy that takes advantage of New Jersey State’s $40 million in tax credits for opening & sustaining new grocery stores in priority areas. Camden’s policy also offers property tax exemptions to businesses operating in these priority areas (see § 753-32). This exemption covers all “improvements” to the property for 10 years. This means a business would pay taxes only on the lot, but not on the building itself – potentially a huge savings.

Unfortunately, a report published 6 years after this policy was codified found that not much had changed. No new grocery stores had opened in Camden. Worse– a corruption scandal hinted that the policy would have been abused to benefit select businesses.

Food Access: More Than Just Physical Barriers

Tax incentives look like easy-to-implement policies. But the verdict is out as to whether they actually succeed. While Prince George’s County’s policy led to the opening of new stores, it’s not clear that this actually improved food access for the community members it was intended for.

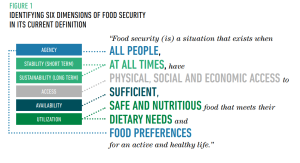

Why is that? Because physical access is only one type of food access. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)’s Committee on World Food Security expanded upon the definition of access in their 2020 report “Food security and nutrition: building a global narrative towards 2030” to include physical as well as social and economic access as imperatives towards achieving food security.

Figure 3: Identifying the Six Dimensions of Food Security

Source: HLPE. 2020. Food security and nutrition: building a global narrative towards 2030. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Rome.

The high cost of quality food in America and the poor job market in these communities has much more influence on an American’s access to food than does distance to a grocery store.

Indeed, a 2015 study found little association between tax credits and improved diet in a Bronx neighborhood where a new market actually opened. This seems to be true across the United States.

This situation leads us to one of the big themes in policy design: developing policy that targets and supports root causes, not symptoms.

Opening new grocery stores in underserved areas seems like a great idea, but if they do not offer social or economic access for the people living in those communities by stocking food that is both affordable and desired, then they are not increasing food access.

So while part of the solution may still be increased physical access to food retail locations, which tax incentives might help, ultimately the solution needs to be as nuanced and multi-faceted as the challenge. Want to be a part of the conversation in Kingston? Keep an eye out for updates on the Food System Plan and consider joining an Eat Well Kingston meeting.